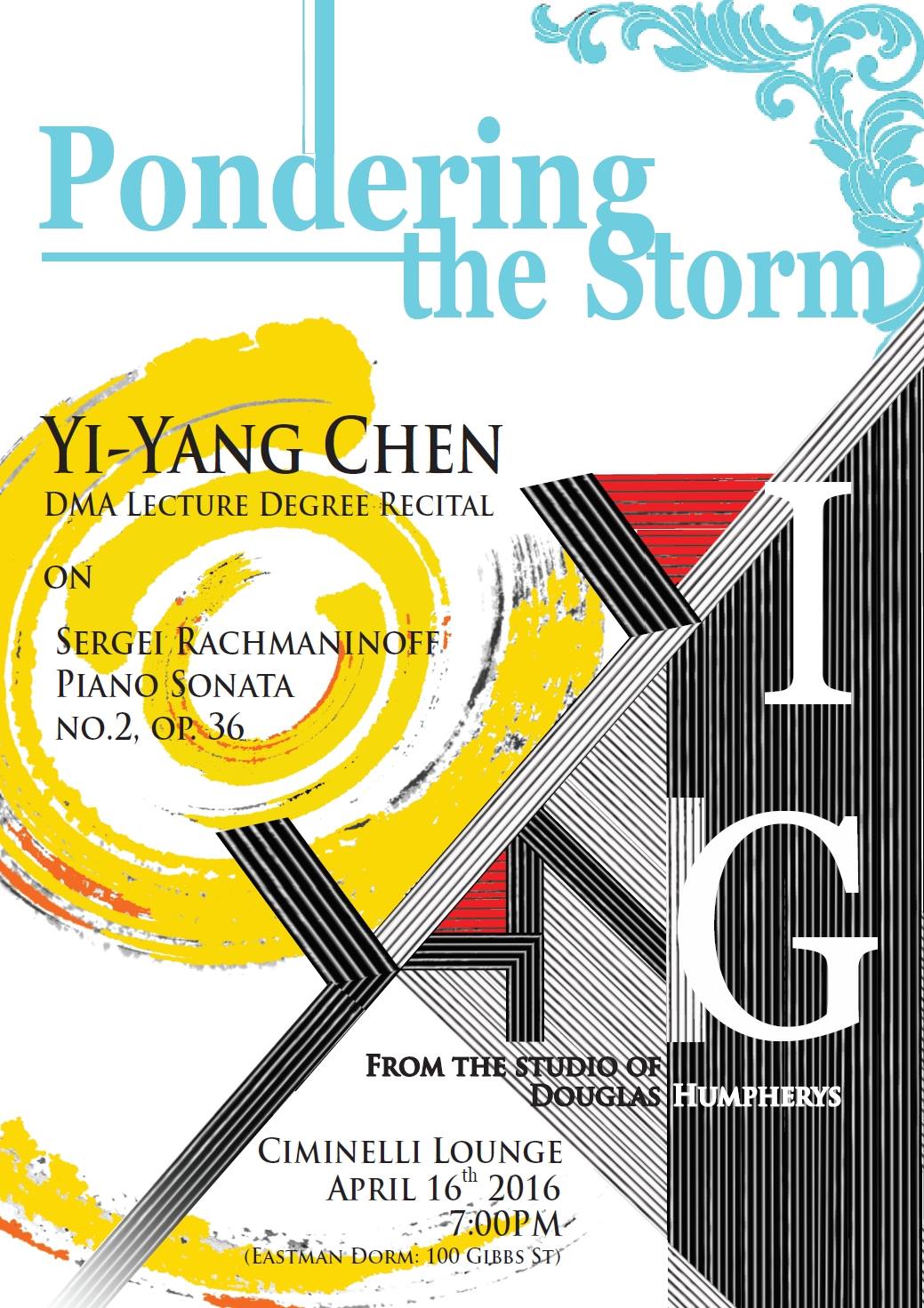

Pondering the Storm:

The Context, Influences, and Revisions of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Sonata No.2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 36

Saturday, April 16th 2016 @ 7:00PM

Ciminelli Lounge

https://www.facebook.com/events/878148548973856/

The Rachmaninoff Second Piano Sonata is no stranger to concert life today. Although not enormous in length, this sonata is striking in its scope and impact. It embraces the full range of the instrument, approaches the dimensions of a symphony, and renders an enormous range of emotions and sensations through its complex textures and polyphony. Because of its glamour it is easy to assume that the sonata was initially well received. However, its journey to popularity was rather slow and hesitant. In order to have a better understanding of this work, we need to consider its social and cultural contexts.

Rachmaninoff composed the sonata in 1913 when he was 40 years old. He had just come back from an American tour and took his family to Rome that summer. He picked up his pen again (he had accomplished little since 1910) and composed in the same flat on the Piazza di Spagna that Tchaikovsky had once occupied. He sketched two works: a choral Symphony based on Edgar Allan Poe’s poem The Bells and the Piano Sonata No.2. The Bells presented special attractions to Rachmaninoff:

The sound of church bells dominated all the cities of the Russia I used to know-Novgorod, Kiev, Moscow. They accompanied every Russian from childhood to the grave, and no composer could escape their influence.

In Rachmaninoff piano sonata No.2, we can hear the reference to bells, and the nostalgia for his home country.

While Rachmaninoff’s setting of The Bells met with success (the composer called it his best composition), the Sonata (premiered in Moscow on 3 December 1913) received a cold reception. Critic Boris Tyuneuev stated:

The sonata is the composition of a mature and great talent … but you will find Rachmaninoff the lyricist in it in only a very small degree – rather the reverse there is a certain inner reserve, severity and introspection. The composer speaks more of the intellect out of the intellect than of the heart out of the heart.

The review might not be fair to a composer embracing a late Romantic idiom in 1913 the same year Stravinsky premiered The Rite of Spring. Rachmaninoff did not return to the sonata after the harsh review until he began his revision of it in 1931. Revising was not a new thing for him. Prior to this sonata, Rachmaninoff had revised other works, including the First Piano Concerto, Second Symphony, and the Isle of the Dead. In the revision of this sonata, he removed more than five minutes of music. Commenting on this process, he said, “I look at my early works and see how much there is that is superfluous. Even in this sonata so many voices are moving simultaneously and it is too long.” Reducing its length and the number of contrapuntal lines makes his musical ideas more direct. Later, in the 1960s, Rachmaninoff allowed his friend Vladimir Horowitz to create his own version that combines elements from both of Rachmaninoff’s versions and some material that Horowitz created himself. Horowitz continuously brought this piece into the spotlight, performing it into his eighties, which helped this sonata gain popularity.

My lecture will be divided into three parts. The first segment will mainly focus on the historical background of the piece, including the influence of Rachmaninoff’s other works on this composition. The second part will give additional social context, explaining why the piece did not get much attention at the time, and considering the problems that led to its revision. The third part will elaborate on the comparison of original and the revised versions. I have chosen the revised version as the norm, and the basis for my comparison, and thus it will be the version that I will perform at the lecture recital.